Dilled Green Tomatoes, Dilly beans, Mild Kimchi all from The Pickled Pantry.The year 2013 may be the year fermentation reached critical mass in America. I’m off to a fermentation festival in Boston next weekend (http://eglestonfarmersmarket.org/fermentation-fest), and there have been other fermentation festivals throughout the summer – almost as many fermentation festivals as music festivals. Fermented pickles are found at almost every farmer’s market and farm-to-table restaurant menus.

Dilled Green Tomatoes, Dilly beans, Mild Kimchi all from The Pickled Pantry.The year 2013 may be the year fermentation reached critical mass in America. I’m off to a fermentation festival in Boston next weekend (http://eglestonfarmersmarket.org/fermentation-fest), and there have been other fermentation festivals throughout the summer – almost as many fermentation festivals as music festivals. Fermented pickles are found at almost every farmer’s market and farm-to-table restaurant menus.

The mainstream health community is catching on to the idea that the billions of microbes we host in our bodies, especially in our guts, are kept healthy and well when we eat plenty of fermented foods with live cultures. Of course, fermented foods with live cultures includes some beers and wine, some sodas, kombucha, yogurt, and miso, tempeh, and more.

So as summer winds down, I am fermenting green tomatoes and dilly beans as a way of dealing with the harvest. We took in about 40 pounds of tomatoes, much of it green when frost threatened. The beans were ready for harvest even if the tomatoes weren’t. Still 10 pounds of snap beans on top of the 10 pounds harvest the week before and the week before means lots of beans to deal with.

The kimchi is less about dealing with the harvest and more about my household’s love of kimchi. It is great tasting stuff – and very “morish” – the more you eat, the more you want.

All of my ferments are made in canning jars. I use a beer bottle sanitizer to clean the jars and all my utensils. Scrupulous attention to cleanliness pays off. My small batches mean that if a jar goes off (which doesn’t seem to happen since I switched to jars), my investment in ingredients and time is minimal. My ferments do age, getting softer and more sourer, but I am more likely to finish a small batch before it gets unpleasant than I am a large batch.

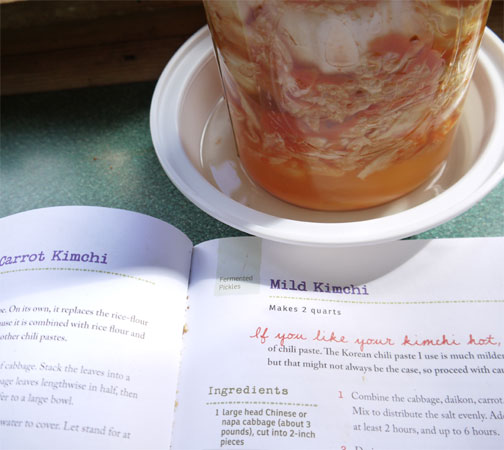

About 1/2 inch of brine as been forced out as the kimchi ferments

About 1/2 inch of brine as been forced out as the kimchi ferments

I fill the jars to the very brim with brine, then cover them with the canning jar lids and screwband. I close the screwband fingertip tight – not ninja, tough-guy tight. Then I put the jars in containers or on saucers. Ferments that make their own brine (kimchi, sauerkraut) will push some of the brine out as they actively ferment. But no air comes in. After the jar is opened and sampled, I continue to make sure the remaining pickles stay under the brine level. mixing up some additional brine to keep everything covered as needed. Once I put the jar in the refrigerator, I don’t worry about the brine levels.

The saurkraut and dilly beans started out in 2-quart jars and are now in pint jars. Moving the ferments to smaller jars reduces exposure to air and extends the life of the pickles.

The saurkraut and dilly beans started out in 2-quart jars and are now in pint jars. Moving the ferments to smaller jars reduces exposure to air and extends the life of the pickles.

This is the recipe for the kimchi I usually bring to workshops for tasting. I have been promising to post it for a while.

Kimchi is "morish." The more you eat, the more you want.

Kimchi is "morish." The more you eat, the more you want.

Mild Kimchi

Makes 1 quart

If you like your kimchi hot, increase the amount of chili paste.

8 cups Napa cabbage, cut into 2-inch pieces

4-inch length daikon radish, peeled and thinly sliced

1 carrot, sliced

½ cup pickling salt

Water to cover

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 tablespoon Korean chili paste

½ teaspoon minced fresh ginger root

½ teaspoon sugar

1. Combine the cabbage, daikon, carrot, and pickling salt in a large bowl. Mix to evenly distribute the salt. Add water to cover. Let stand for at least 2 hours, up to 6 hours.

2. Drain, reserving the brine. Add the garlic, chili paste, ginger, and sugar to the cabbage mixture and mix well.

3. Pack the mixture into a clean 1-quart canning jar. Add enough brine to cover the mixture and fill to the top. Cover to exclude air.

4. Set the jar on a saucer where the temperature will remain constant: 65° to 75°F is ideal.

5. Begin tasting after 3 days and refrigerate when the kimchi is pleasantly sour. The kimchi continue to age and develop flavor. Store in the refrigerator. It will keep for several months.

Recipe adapted from The Pickled Pantry. ©2012 Andrea Chesman. All rights reserved.